[ad_1]

Whenever that what this article is about comes to my mind the ‘inbuilt music player’ in my head is turned on and one of the most famous Reggae songs from the late 1960s starts to play. It is a song that is opening and warming the hearts of all those who have in the times of Eddy Grant’s “Baby Come Back”, Desmond Dekker’s “You Can Get It If You Really Want” and Tony Tribe’s “Red, Red, Wine” discovered the world of love and have had their first serious love affairs with their ‘One-and-Only’. Do you remember these times and your first serious love affair? The song now playing in my head is “Black Pearl”. Can you hear it? “Black pearl, precious little girl, let me put you up where you belong, because I love you.” Well, this article is about black pearls too, but black pearls of a different kind and it is not confined to them’.

Burma, the country I call home since more than 25 years, has once played a notable role in the global pearl industry and some of the world’s largest and most precious pearls have been discovered in the waters off the Burmese coast. However, since 15 years Burma is back on the stage of international pearl business and increasingly successful with its unique silver and golden South Sea Cultured Pearls.

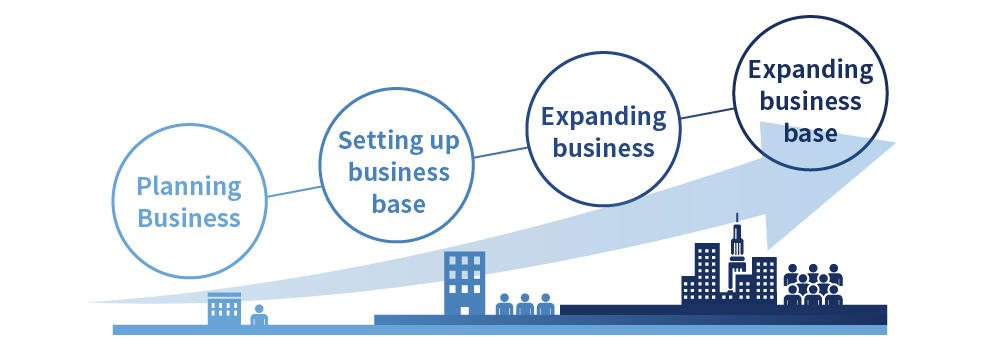

The history of the Burmese Pearl Industry begins back in 1954 with the Japanese K. Takashima who has founded a joint venture between the Japanese ‘South Sea Pearl Company Ltd.’ and the ‘Burma Pearl Diving and Cultivation Syndicate’ as local partner. The same year South Sea Cultured Pearl production with Pinctada maxima was started in the Mergui Archipelago and the first pearl harvest took place in 1957. This harvest was a great success. The pearls belonged to the group of finest South Sea Cultured Pearls and fetched highest prices. Within a few years Burma had earned itself a good reputation as producer of South Sea Cultured Pearls of highest quality and remained in the world’s top group of South Sea Cultured Pearl producing countries till 1983 when reputedly in consequence of a bacterial infection Burma’s pearl oyster stock was almost completely extinguished. Burma’s Pearl Industry recovered very gradually and for more than a decade its pearl production remained negligible and the pearl quality rather poor. However, from 2001 on Burma’s South Sea Cultured Pearl production is gaining momentum and quantities of high quality cultured pearls are continuously increasing.

Now, in early 2016, there are 1 government owned company, 4 privately owned local companies and 4 foreign companies (joint ventures) representing the Burmese pearl industry. They are culturing pearls mainly on islands of the Mergui Archipelago and Pearl Island and are on a good way to regain Burma’s formerly excellent reputation and help the country to play an increasingly important role as pearl producer in the global South Sea Cultured Pearl market. Not necessarily in terms of quantity but surely in terms of premium quality. Burmese pearl companies are already getting more and more attention in the international pearl market.

OK, let us now focus on the central theme and star of this article: the Pearl.

At the beginning of this article I spoke of love in connection with pearls and pearls are indeed something wonderful to express love with. However, the story of a pearl’s coming into being might not exactly be one of love but – imagining the pearl-producing shelled mollusc can feel pain – at least at its beginning rather a story of pain because something that does not belong there has entered into the mollusc’s living tissue. In other words, a pearl is the result of the defence against a painful hostile attack. It’s as if the thorn of a rose has lodged itself into your thumb; ouch! But that is exactly how the life of a pearl begins, with something that manages to sneak into the shell of a mollusc and to forcibly enter its soft tissue. This ‘something’ can be e.g. a larva of a parasite or a tiny grain of sand.

Question: “What is a pearl?” A pearl is something relatively hard and usually silvery-white that is either round or of irregular shape. Its nucleus is an ‘intruder’, which the pearl-producing mollusc has first coated with a pearl sac around which it has then deposited layers of microscopic small crystals of calcium carbonate called ‘nacre’ in order to isolate the foreign object called ‘irritant’. Between the layers that make up the pearl are layers of the organic compound conchiolin that glues them together and at the same time separates them. The process of producing these nacre layers is never ending what means that the older the pearl is, the larger is the amount of its layers and, subsequently, the bigger it is. This is the answer to the question.

“And that is all?” you may now ask. Well, basically, yes but there is, of course, much more to the topic ‘pearl’. Keep on reading and you will know. Let’s take a peek into the history of pearls and pearl business and go back to the beginning.

It was probably 500 BC (perhaps earlier) that people focused more on the contents than the wrapping and started to appreciate the beauty of pearls more than the mother-of-pearl of their producers’ shells. Consequently, they placed the best of the pearls at one level with ‘gemstones’ and attached high value to them in immaterial terms (power and beauty) and material terms (wealth).

Pearls are also called ‘Gems of the sea’ but unlike any other gem, a pearl is the product of a living being. That is, pearls are the only ‘gems’ of organic origin, which is exactly how gemmologists classify pearls in general: as ‘coloured gems of organic origin’. And pearls are the only ‘gems’ that require no cutting or polishing – just cleaning – before they display their full beauty.

Back then pearls only existed in the form of natural also called wild pearls. They were therefore very rare and being a symbol of power, wealth and beauty much sought after by royalties and non-royalties who could afford and were willing to pay astronomical prices for them. In other words, the demand for pearls – either singly, as so-called collectors’ item or as part of jewellery – was very high and the supply very low what made a special category of pearls a highly priced luxury article and the trade with these pearls an extremely profitable business. Fuelled by three of mankind’s strongest motives – to be wealthy, powerful and beautiful – the hunt for pearls by sellers and buyers alike had begun.

Let’s take a second, closer look at pearls and their natural creators. Basically, almost all kinds of shelled molluscs (even some species of snails!) can irrespective of whether they are populating bodies of freshwater such as rivers and lakes or bodies of saltwater such as seas and oceans create pearls what is a process called ‘calcareous concretion’. However, the vast majority of these pearls are of no value at all except maybe from the viewpoint of a collector or scientist. Exceptions to this rule are, for instance, the ‘Blue Pearls’ of abalone shells and ‘Pink Pearls’ of conch sea snails

The differences between valuable and worthless pearls are in a combination of their size, weight, form, lustre, colour (incl. nacreousness and iridescence) as well as conditions of the surface. These are the criteria that determine on whether or not a pearl is of gem quality and can fetch highest prices. Only this category of pearls is of interest to the long chain of those being involved in pearl business from pearl diver to pearl seller on the supply side and, of course, the buyer on the demand side.

Those pearls that make it into the top group of gem-quality pearls are created by only a few species of mussels and/or pearl oysters. Freshwater pearls are created by members of the fresh water mussel family ‘Unionidae’ whereas saltwater pearls are created by members of the pearl oyster family ‘Pteriidae’.

Till 1928 when the very first set of cultured pearls was produced and introduced to the pearl market by Mitsubishi Company/Japan there were only natural pearls on the market. This kept the number of commercially valuable pearls small and their prices extremely high. This was especially true for ‘ideal’ pearls that were perfectly round and fetched the highest prices.

Since formulations such as ‘high value’ or ‘high prices’ are relative and have not much in the way of meaning I feel the need to attach a figure to them. The following example will give you an idea of the value of pearls in ‘pre-cultural’ pearl times. A matched double strand of 55 plus 73 (in total 128) round natural pearls from jeweller Pierre Cartier was valued in 1917 at USD 1 million. Factoring into the calculation an annual average inflation rate of 3.09 % the pearl strand’s present-day monetary value would be USD 20.39 million! I am sure that after having taken a deep breath you have now a very good picture of what values I am talking with respect to pearls especially when it comes to natural pearls prior to the emergence of cultured pearls. And by-the-by, natural pearls will always be the most precious and valuable, even in the era of the cultured pearl. Why? This is so because these pearls are pure nature and absolute unique especially when we add the factor antiquity.

With the commercialisation of the by the British biologist William Saville-Kent developed and the Japanese Tokichi Nishikawa patented method to produce cultured pearls the pearl industry was revolutionised and has experienced most dramatic changes. A cultured pearl industry based on the new process developed in Japan and things changed drastically. Nothing would ever again be as it was.

Pearl culturing made the mass production of ‘tailor-made’ pearls of prime quality possible. Because the ‘How To’ was kept secret and not allowed to be made available to foreigners It also gave Japan the global monopoly of cultured pearls, thus, the world-wide dominance of and control over the pearl industry, which, among others, allowed the manipulation of pearl prices by controlling the amount of pearls made available; much like the De Beers diamond syndicate controlled the global diamond market. Prices dropped and the purchase of pearls that was affordable prior to the availability of cultured pearls only to a lucky few was now possible for a very large number of financially better off people; demand for pearls exploded and Japan’s pearl industry started to boom and made enormous profits through direct sales of large amounts of cultured pearls, licences and shares in business enterprises with foreign companies. Nowadays, this has changed and there are more cultured pearl producing countries; some, like China, do occasionally sell their cultured pearls (especially freshwater pearls, at a price of 10% of that of natural pearls what allows almost everyone to buy pearls and/or pearl jewellery. However, since the supply will never meet the demand for pearls their prices will always remain high enough to ensure that pearl business remains to be ‘big business’.

Different Kinds Of Pearls

Pearls are classed as Akoya Pearl, South Sea Pearl, Tahitian Pearl, Freshwater Pearl and Mabé Pearl or Blister Pearl (Half Pearl). In this article I will deal primarily with the first three of them for these pearls are the most precious and for this reason those with the highest commercial value.

Akoya Pearls

Akoya Pearls are created by an oyster of the family Pteriidae that Japanese call Akoya oyster. The Latin name of it is Pinctada fucata martensii. There is no translation of the name Akoya into English and also the meaning of the word Akoya is not known.

An Akoya pearl was the first ever cultured pearl. With a size of 2.4 to 3.1 in/6 to 8 cm the Akoya oyster is the world’s smallest pearl-producing oyster. Accordingly small is its pearl the size of which ranges depending on its age between 2 and 12mm. The average diameter of an Akoya pearl is 8 mm. Akoya pearls with a larger diameter than 10 mm are very rare and sold at high prices.

It takes a minimum of 10 months from the time of seeding on till an Akoya Pearl is ready to be harvested. Usually the oysters stay for to 18 months in the water before they are harvested. The Akoya oyster produces 1 pearl in its lifetime. After that it is provided it has produced a good pearl used as tissue donor.

The pearl’s shape can be all round, mostly round, slightly off round, off round, semi-baroque and baroque and its colour can be white, black, pink, cream, medium cream, dark cream, blue, gold or gray. The pearls come with different overtones, are mostly white and their lustre is exceptionally brilliant second only to the lustre of South Sea Pearls. The Akoya Pearl is cultured primarily off the Japanese and Chinese coast.

The ideal water temperature for Akoya oysters is between 15 and 23oC/59 and 73.4 Fahrenheit.

South Sea Pearl

South Sea Pearls are created by an oyster of the family Pteriidae. It is a white-lipped, silver-lipped or gold-lipped pearl oyster. The Latin name of it is Pinctada maxima.

Cultured South Sea Pearls are one of the rarest and therefore most valuable of cultured pearls. With a size of up to 13 in/32.5 cm the South Sea Oyster is the world’s largest pearl-producing oysters. Accordingly large are its pearls the sizes of which range depending on age between 8 and 22+ mm, but the average diameter of South Sea Pearls is 15 mm and Cultured South Sea Pearls exceeding a diameter of more than 22 mm are something like the jackpot in the State Lottery.

It takes at least 1.5 years from the time of seeding on till a South Sea Pearl is ready to be harvested for the first time. Usually the oysters stay for 2 to 3 years in the water before they are harvested to get larger pearls. The oyster produces 2 to 3 pearls in its lifetime. After that it is too old and is provided it has produced good pearls used as tissue donor.

The pearl’s shape can be round, semi-round, baroque, semi-baroque, drop, button, oval, circle and ringed and its colour can be white-silver, white-rose, blue-white, light-cream, champagne (medium cream) and gold. However, the most sought after are silver and gold. The South Sea Pearl is highly lustrous with a slight satiny sheen.

The South Sea Pearl is cultured primarily from the Indian Ocean to the Pacific. Cultured South Sea Pearl producing countries are Australia, New Guinea, the Philippines, Indonesia and Burma.

The ideal water temperature for South Sea Pearl oysters is between 73.4o-89.6o F/23°C-32°C.

Tahitian Pearls

Tahitian Pearls are created by an oyster of the family Pteriidae that is called the black-lipped pearl oyster. The Latin name of it is Pinctada margaritifera.

Tahitian Pearls commonly known as black pearls belong to the group of rare, most valuable cultured pearls and are increasingly in demand. With a size of up to 12 in/30 cm the Black Pearl Oyster is the world’s second largest pearl-producing oysters. Accordingly large is its pearl the size of which ranges depending on age between 8 and 18 mm, but the average diameter of Tahitian Pearls is 13 mm.

It takes at least 1.5 years from the time of seeding on till a Tahitian Pearl is ready to be harvested for the first time. Usually the oysters stay for 2 to 3 years in the water before they are harvested to get larger pearls. The oyster produces 2 to 3 pearls in its lifetime. After that it is provided it has produced good pearls used as tissue donor.

The pearl’s shape can be round, slightly off round, semi-round, button, and pear, drop, oval, semi-baroque, baroque and ringed.

Although the Tahitian Pearl is called ‘Black Pearl’ most of them are not really black. Their colours range from dark anthracite, charcoal gray, silver gray to dark blue and dark green with each colour having distinctive undertones and overtones of green, pink, blue, silver and even yellow.

The Tahitian Pearl’s lustre is very high with brilliant and bright reflections.

It is cultured from the Indian Ocean to the Pacific but primarily off the coasts of Tahiti and the French Polynesian Islands. However there have been reports of Pinctada margaritifera in the Red Sea, off the coast of Alexandria (Egypt) and Calabria (Italy).

The ideal water temperature for the Black Pearl oysters is between 73.4o-84.2o F/23°C-29°C.

Freshwater Pearls

What used to be the main difference between cultured seawater pearls and cultured freshwater pearls is that contrary to cultured seawater pearls cultured freshwater pearls were not beaded and pure nacre for which reason they are called non-beaded cultured pearls. This, however, does not apply fully anymore. Since the Ming Pearl, official name ‘Edison Pearl’, was introduced into the market by the Chinese in January 2011, freshwater pearls do now also have a very beautiful representative in the category ‘Cultured Beaded Pearls’.

Non-beaded freshwater Pearls are created by 3 species of mussels of the family Unionidae. One of these is called Triangle Sail Mussel with the Latin name Hyriopsis cumingii, the other one is called Biwa Pearl with the Latin name Hyriopsis schlegelii and the third one has the Latin name Christaria plicata and is called Cockscomb Pearl Mussel.

Beaded Freshwater Pearls or as they are properly called ‘ in-body bead-nucleated freshwater pearls’ are produced by a hybrid form of Hyriopsis cumingii and Hyriopsis cumingii.

Freshwater Pearls are increasingly in demand. Their sizes range from tiny seed pearls measuring 1 to 2 mm in diameter to 15 mm and larger.

It usually takes 3-5 years from the time of seeding on till a non-beaded freshwater mussel is ready to be harvested. Some stay in the water for up to 7 years to produce larger pearls. However, this slow pearl growth is more than compensated by the fact that one mussel can produce up to 40+ pearls at the same time. Usually the mussel produces 1 set of pearls in its lifetime. After that it is provided it has produced good pearls used as tissue donor.

For the beaded cultured freshwater pearl, the Edison pearl, it takes 4 years to be formed to a pearl with a diameter of 15+mm in the Hyriopsis cumingii/Hyriopsis cumingii hybrid. The mussel can only produce one pearl at a time.

The pearl’s shape can be round, slightly off round or near round, off round, semi-round, button, coin, pear or drop, oval, semi-baroque, baroque and ringed and any kind of irregular shape such as ‘rice krispies’.

Their colours range from white to natural pastel colours such as champagne, lavender, pink, blue and every shade in between.

The Freshwater Pearl’s lustre is high with bright reflections.

Freshwater Pearl’s are cultured globally but primarily in Chinese, Japanese and to a much lesser extent in USA lakes and rivers. The world’s largest producer of freshwater pearls is China.

The ideal water temperature for freshwater pearl mussels is depending on spices between 68 o F- 82.4 o F/20°C-28°C.

Other Types of Pearls

Keishi Pearls

Keishi Pearls can be found in both saltwater and freshwater shelled molluscs. They are the result of oysters’/mussels’ ejecting of irritants prior to the moment the pearl has completely coated the implant with nacre. In this case the irritant is separated from the pearl sac and a freeform pearl without nuclei develops. Keishi pearls are as the name implies (Keishi means ‘small’ or ‘tiny’ in Japanese) usually small, made of pure nacre and irregular in shape. A Keishi pearl’s colour ranges from silvery pure white to silvery grey and every variation between.

Mabé Pearl or Blister Pearl

Unlike other pearls that grow within the living tissue of the oyster, the pearl of the Mabé oyster is in the habit of attaching itself to the inside of the oyster shell and grow there as ‘half pearl’ what makes them look like a blister what is the alternative name used for this kind of pearl ‘Blister Pearl’. When the pearl is harvested it is skilfully cut from the shell and after removing the implant the hollow part is filled with a special wax prior to the backside’s being artfully finished off with mother-of-pearl. As for colours these cover predominantly a wide range of white and attractive silvery pastel tones.

The question now is what exactly these cultured pearls that had such an earth shattering impact on the global pearl industry are, in the first place?

Cultured Pearls

It is of the utmost importance to know and understand that a cultured pearl is not an artificial pearl or imitation pearl. On the contrary, a cultured pearl is a natural pearl in so far as the pearl is the result of the same natural process that takes place in wilderness; a foreign object is entering the oyster or mussel shell, is lodging itself in the oyster’s/mussel’s living tissue, the shelled mollusc’s defence mechanism is triggered and the intruder is enclosed in layers of calcium carbonate and conchiolin. The final result is a pearl.

What we are speaking about when comparing natural to cultured pearls are actually two things. Firstly, the event that triggers the pearl’s coming into existence and, secondly, the final result of this event. The bottom line is that the differences between a natural and a cultured pearl is a very small one and confined to the event that initiates the development of a pearl.

For the purpose of this article I like to speak of that to what the shelled mollusc responds with the creation of a pearl in reproduction terms and say that it is ‘the way of fertilisation’ that makes the difference between ‘natural’ and ‘cultured’. In the wilderness the entering of the irritant happens accidentally and without human beings being involved whereas in a pearl farm this happens with human beings being involved by way of a surgical operation known as ‘grafting’. Phrased in reproduction terms we can call it ‘artificial fertilisation’. I will briefly explain the process of grafting later. Everything that follows the inserting of the irritant i.e. the process of the development of the pearl within the oyster is purely natural.

Having the possibility to produce cultured pearls is something both pearl oyster and of course its owner in the first place do hugely benefit from. The oysters’ advantages are that they are for whatever it is worth growing up and living in a controlled environment in which they are to a large extent protected from sickness and natural enemies and the oysters owner’s advantages are that he can e.g. determine how many and what kind of pearls he wants to produce, when the host oysters are starting to create the pears, what shape the pearls will have, what their colour and lustre will be and what their size will be, i.e. when they will be harvested.

The huge advantages to producing cultured pearls compared to diving for wild oyster pearls in areas with oyster beds in the hope to find a commercially valuable natural pearl should by now have become very obvious. Statistically there is on average one marketable pearl in 1.000 wild oysters. This means that if you are not very, very lucky, to borough from the golfer jargon, the ‘Jackpot-In-One’ type, you will most likely have to find thousands of natural pearls oyster, open and in doing so kill them before you may find one commercially valuable pearl of the species you are after. This is a very risky, troublesome, time consuming, costly and in the long term environmentally harmful affair. For this very reason the process of culturing pearls was developed.

It all began with the British Mr. British biologist William Saville-Kent (1845 -1908) who was in 1894 successful in developing a method to produce cultured pearls and the Japanese marine biologist Dr. Tokichi Nishikawa (1874-1909), the Japanese carpenter Mr. Tatsuhei Mise (1880-1924) and the Japanese vegetable vendor Mr. Kokichi Mikimoto (1858-1954), who patented and further developed and commercialised the process of producing cultured pearls that became known as ‘The Mother Of Pearls’ (not to be confused with mother-of-pearl, oysters and mussels are lining the insides of their shells with) the ‘Akoya Pearl’. Natural pearls would continue to decorate only a privileged few if not for the ingenuity of three Japanese men

In 1902, Tatsuhei Mise implanted 15,000 molluscs with lead and silver nuclei and two years later, harvested small, round cultured pearls. In 1907, he received the first ever Japanese patent for the production of a round cultured pearl.

Around the same time, Dr. Nishikawa began seeding oysters using tiny gold and silver nuclei. His process also yielded small round cultured pearls. He applied for a patent that was restricted to the implantation process that was uncannily similar to Mise’s. As the two processes were nearly identical, it became known as the Mise-Nishikawa method.

Pearl Farming

Something going hand-in-hand with producing cultured pearls or more precisely phrased is integral part of the overall process of most efficiently and effectively producing cultured pearls is pearl farming. After all, it does not make much in the way of sense to dive for natural pearl-producing oysters that are often to be found in depths of 60 to 85 feet, to collect them individually, take them to the surface, clean them, graft them, mark them, return them to the oyster bed only to dive for them again later in order to harvest the pearls. I believe we do all agree that operating this way would be the most inefficient and ineffective way imaginable to produce cultured pearls. So, the proper way of doing it is pearl oyster farming. But however much pearl farming and hatching has been developed and improved technically and otherwise especially in the last 10 years it still remains a risky undertaking and depends as much on skill as it depends on luck. Why luck? Luck, because there are so many very serious natural and manmade threats inherent in pearl farming that are completely or at least to a large extent out of human control. Examples of these are extreme changes in water temperatures, pollution of water with wastewater both industrial and domestic, diseases such as the one caused by ‘red tide’, unusual strong storms and water movement, siltation and several natural predators for pearl oysters such as echinoderm (star fish, sea-cucumber), gastropods (snails and slugs), turbellaria (flatworms) and rays and octopuses, just to name a few of the most common natural and manmade threats. That is why I advice you not to fool yourself when reading the following brief descriptions. All sounds smooth and well on paper but things are by far not as easy as they may appear.

Here comes how pearl farming works by example of Pinctada maxima producing South Sea Cultured Pearls.

Pearl Oyster Hatching

The modern cultured pearl industry is for biological and economic reasons to an increasing extent stocking oyster farms with hatched oysters. The hatching process begins with the selection of for hatching suitable pearl-producing oysters from the wilderness or from hatchery produced oysters and ends with the oysters’ being ready for producing pearls. When the suitable male and female oysters are found they are placed into spawning tanks filled with saltwater. Now the water temperature is increased what sets into motion the following process.

Male oysters are stimulated to spawn, the sperm stimulates female oysters to release eggs, the eggs are fertilised, the fertilised eggs are collected and incubated in seawater tanks to allow larval development, when larvae have developed they are counted, transferred to and fed in clean larval culture tanks. After 22 days the larvae are collected and transferred into tanks with settlement substrate to allow the larvae to attach themselves and develop into oyster spat. Once the spat has reached a shell thickness of min. 6 mm is placed into fine mesh as protection for predators and transferred into the raft suspended in the ocean water of the farm. Grown larger to sub-adults they are placed into bigger mesh were they grow to adults. After 2 years the oysters are ready to produce pearls and will be grafted for the first time.

The Grafting Of Pearls Oysters

The grafting of a pearl oyster begins with the selection of a suitable wild or farm oyster and ends with its being returned to the water i.e. to the oyster farm. The steps between are the choosing of the right period for the grafting, the proper preparing of the oyster for the grafting (less food, anesthetising), the selecting of a suitable implant and graft tissue, the professional performing of the surgical operation and a proper follow-up care of the oyster after the surgery before it is released back into the water. This process is an important one with the surgical operation being the most important part of it for it determines to not a small degree on death rate of the oysters after surgery, rejection of the implanted nucleus and the overall quality of the final pearl. That is, the grafting can make it or break it.

[ad_2]

Source by Markus Burman