[ad_1]

Ottawa, Jul 19 (IPS) – Toronto resident Miranda Knight describes her abortion experience as relatively simple. After finding out she was pregnant on a Wednesday in 2017, she booked an appointment at an available clinic and got one for the following Monday. She had the procedure that day and left the clinic by noon.

But Knight’s experience is not the reality for all. As Canada’s most populous city, Toronto has several access points to abortion. Despite abortion being legal nationwide since 1988 and officially treated like any other medical procedure, many other parts of the country do not have access points.

The United Nations has highlighted this disparity. A 2016 report from the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women encouraged the Canadian government to improve the accessibility of abortion services nationwide.

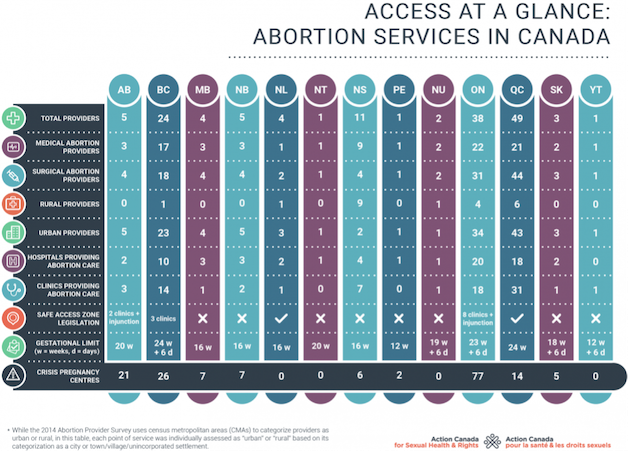

According to the Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada (ARCC), fewer than one in five hospitals offer the procedure.

ARCC Executive Director Joyce Arthur said access could be a real struggle for those living outside cities or far from the US border. Most access points are found within less than 150 kilometers of a town, where most Canadians live.

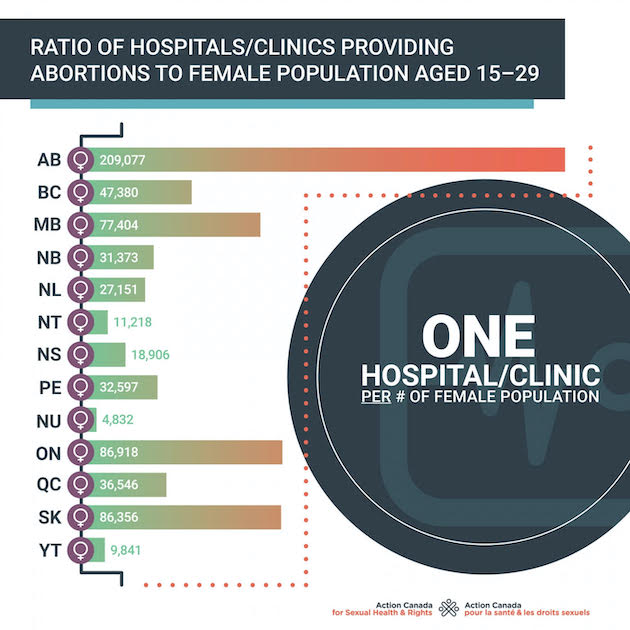

“As soon as you’re away from the city, or up north, you often might have to travel for services, sometimes hundreds of kilometers, and even sometimes for medication. Access is pretty good in British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec , but the rest of the provinces only have one or two or three or four access points. It’s just not enough,” she said.

Abortion access differs by province partly because healthcare in Canada is a provincial responsibility. According to 2019 figures, Quebec has the highest number of access points with 49 province-wide, while Newfoundland and Labrador have four and Saskatchewan has three.

Healthcare disparities among rural and urban communities are a significant issue in Canada—especially considering the country’s geography. But Arthur told IPS that unequal abortion access went beyond that.

“Canada is a really big country geographically, so other health care procedures might be hard to access, and people have to travel sometimes. But abortion is a very simple procedure. Early-first trimester abortion can be done on an outpatient basis and doesn’t really require a lot of special equipment. Why aren’t more hospitals doing it?”

Arthur believes the culprit is stigma from the anti-choice movement.

“Much of this is due to remaining abortion stigma from before it was de-criminalized. The anti-choice movement has continued to play a big role in reinforcing that stigma and instilling fear in providers. There’s still this feeling of silencing and shame, which comes from abortion stigma,” she said.

Arthur explained it was not that long ago that doctors would get shot for performing abortions in Canada. From the late 1970s until the mid-1990s, there were several instances of violence against physicians in their own homes.

“That permeates on various levels, not just at the level of the doctor or the patient, but also in government and in medical organizations who would rather just not have to deal with abortion and not have to think about it,” she said.

Disparities in access have led community organizers to step up and help those in need get care.

Shannon Hardy, a birth doula, founded Abortion Support Services Atlantic (ASSA) in 2012 after encountering issues related to abortion access across the Atlantic provinces.

“Some things came across my desk about lack of access in Prince Edward Island. And I didn’t actually know that PEI didn’t offer abortion services, like the entire island for 32 years just didn’t offer it. It kind of blew my mind,” she said.

People wanting to terminate their pregnancy can contact ASSA for information, peer support, transport to abortion clinics, or even financial help for travel. In these cases, Hardy told IPS that ASSA would often fundraise to pay for gas, hotels, or flights.

Support services are beneficial for those encountering stigma, Hardy said.

“When a person is facing an ill-timed or unwanted pregnancy, they can immediately feel a stigma around seeking abortion care. Who is safe to reach out to? Will people judge me? Will my doctor/medical center offer me care? My goal for creating ASSA was to have a place where anyone seeking abortion care could reach out and help would just be there.”

Hardy’s work has spearheaded a movement. Many other doula organizations have popped up across the country with a similar model. They also often collaborate with national abortion advocacy organizations to help people access the procedure in circumstances that require on-the-ground coordination and support.

Yet, Hardy believes that the need for organizations like ASSA point to critical access issues across the country and inaction at government levels.

“It’s been frustrating that there’s not more access. We, as a grassroots organization, are the ones responsible for getting people from one small town to access abortion instead of the healthcare system stepping in and saying, ‘you know what, we actually have the resources to offer that medical service. So, we’re just going to do that to make life easier’,” she said.

Working in Alberta, one of Canada’s most socially conservative provinces, Autumn Reinhardt-Simpson is familiar with how attitudes on abortion can impact care. She founded Alberta Abortion Access Network to help those across the province in 2015.

Reinhardt-Simpson told IPS that those in rural areas face increased access issues because their care is more dependent on the “private moral concerns” of the health care professionals in their area.

This can make trying to get an abortion more complicated, she explained. Many physicians and pharmacists are either unwilling to offer reproductive health services or unaware of their legality.

In one case, Reinhardt-Simpson had to visit ten different pharmacies to find one that stocked Mifegymiso—the abortion pill that became legal in 2017.

“They were saying things like, ‘Oh well, we can’t dispense this, or this isn’t legal yet. Or well, we can’t get the medication.’ And it’s like no, no, that’s not how this works,” she said.

Alberta has only four access points for surgical abortions, all in its cities. Along with another helper, Reinhardt-Simpson services the whole of Alberta’s 661,848 km² (411, 253 mi²) and helps people access abortion services.

In her view, the stigma around abortion care is detrimental. It can even be physically harmful—particularly for those in later trimesters desperate for solutions.

“The stigma is preventing thousands of Albertans from receiving critical and routine health care. Because there are so many hoops to jump through, some people will get tired of those hoops, and they will try to do something themselves. It doesn’t usually end well. the stigma is physically dangerous, it’s emotionally harmful, and culturally it does us no good,” she said.

Being familiar with reproductive justice issues as a community organizer, Knight feels compelled to share her abortion story to combat stigma and normalize the procedure.

She’s currently developing a storytelling project that will feature diverse abortion experiences. Knight told IPS the project’s proceeds would go to improving access across Canada. She hopes to help to improve access for others, considering how essential the procedure was for her.

“My prevailing feeling about the whole thing was just relief. I don’t want to live in an alternate universe where I didn’t have access to abortion. My life would be very different now,” she said.

IPS UN Bureau Report

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2022) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

[ad_2]

Source link