[ad_1]

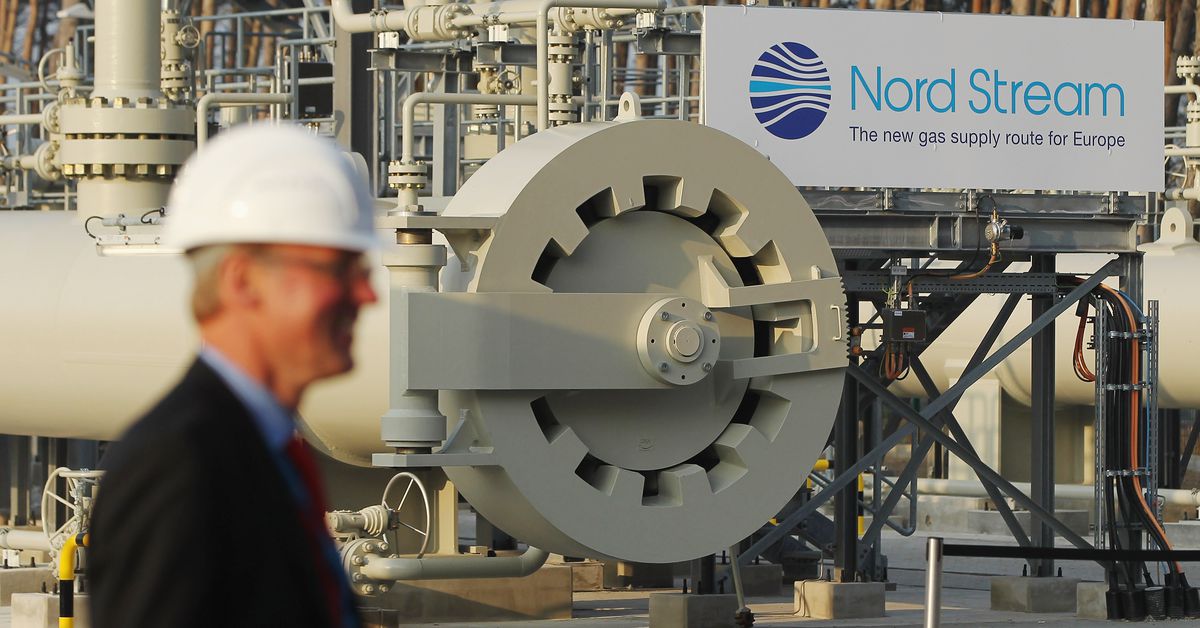

Nord Stream 1, the pipeline that delivers natural gas from Russia to Germany, is shut down as it undergoes annual maintenance. Typically, this is routine. But typically, a war isn’t raging in Europe.

That’s why Germany — and the rest of the European Union — was nervous that when that 10-day maintenance was scheduled to end on July 21, the pipeline wouldn’t come back online. Instead, Russia may keep it closed, or drastically reduce the flows that run through it, as retaliation against Germany and the rest of Europe for sanctions and their support for Ukraine.

A Nord Stream 1 shutdown would lead to even more economic disruption on the continent, and a harbinger for a long, cold, and tumultuous winter. Europe before the war got about 40 percent of its gas from Russia, mostly through pipelines; Germany relies on Russia for about a third of its gas imports. Russian President Vladimir Putin has suggested that the pipeline will resume deliveries, but at far below capacity.

Russia had already reduced and reduced the amount of natural gas it exports to Europe in recent weeks. In June, the Russian-state owned gas company Gazprom slashed the amount of gas delivered through Nord Stream 1 by 60 percent, a decision it blamed on the West, saying a necessary turbine was out for repair in Canada but stuck there because of sanctions. Experts said this was a pretext, and a pretty flimsy one at that, but it still got Germany and Canada to act.

It is already getting difficult to insulate Germany’s economy, and Europe’s more broadly, from Russia’s energy threats — and that is further destabilizing the global economy.

Even as European leaders have sanctioned Russian coal, started phasing in sanctions on seaborne Russian oil, and vowed to reduce Russian natural gas imports, Europe has struggled to wean itself off Russian energy, particularly natural gas. Europe is seeking alternatives but is finding it hard to secure speedy and affordable replacements for what once flowed easily via pipeline. European countries have also set storage targets for natural gas to head off disaster this winter, but Russia’s decrease in deliveries has made those already ambitious goals much harder to reach.

On Wednesday, the European Union confronted this crisis, putting itself on almost wartime footing with an emergency plan to reduce gas consumption on the continent to avoid more dramatic shortages this winter, even as the current heat wave is exacerbating the continent’s energy crunch. The proposal calls on EU countries to ration gas and decrease usage by about 15 percent across the bloc.

“Russia is blackmailing us. Russia is using energy as a weapon,” said European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen on Wednesday.

Europe’s reliance on Russian gas has always been a weapon available to Russian President Vladimir Putin, and now he is wielding it. Putin may believe that energy pressures — fuel price increases, households unable to heat their homes, industry floundering, and all of it hastening a recession — could exploit cracks in the Western alliance and tear apart Europe itself.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23889900/GettyImages_1241910074.jpg)

Putin is using his “point of maximum leverage to try to obtain the greatest concessions,” said Jeff D. Makholm, managing director of NERA Economic Consulting. “And the point of maximum leverage is in the lead up to the winter of 2023.”

Europe knows this, which is why it has sought to move away from Russian energy any way it can. That looks like it’s going to happen — just not quite according to the original plan. “It’s not the European countries which have basically managed to reduce the imports of Russian gas,” said Anne-Sophie Corbeau, global research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University. “It’s Russia.”

Russia has been progressively reducing gas. Then it came for Nord Stream 1.

On Wednesday, von der Leyen said that at least 12 countries have been hit by a partial or total gas cutoff, and the amount of gas flowing to Europe is less than one-third what it was this time last year.

Russia’s delivery slowdown is already disrupting European industries, forcing some factories to shut down. One of Germany’s largest energy providers is seeking a bailout from the government; reductions in gas could eventually bring certain factories to a standstill. These cutbacks are also likely to hurt smaller, less wealthy European countries even more, especially those that are more dependent on Russia and have fewer resources to deflect a crisis. Germany is encouraging people to take shorter, colder showers; Berlin has turned down the temperature on its swimming pools. “It’s better to have a cold shower in summer than a cold apartment in winter,” said Jürgen Krogmann, the mayor of Oldenburg, a city in northwestern Germany, according to the Washington Post.

The fear of a complete cutoff of Russian gas has intensified Europe’s urgency to head off this crisis, one that has been months (or, arguably, decades) in the making. Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Russia had not increased gas deliveries to meet European demand and, in the months since the war began, has gradually tightened the tap. At the same time, Europe, along with other allies, put punishing sanctions on Russia and made very clear it wanted to target Russia’s energy sector, while also trying to minimize some of the pain to its members.

“The more Western leaders threaten to sanction Russian oil exports in whatever form they’re going to sanction it, the more the Russians will shift the battleground to gas,” said Edward Chow, nonresident senior associate fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “Because for Europe, Russian gas as a whole is a lot harder to replace than it is to replace Russian oil.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23889869/GettyImages_1241833174a.jpg)

Nord Stream 1 is the battleground of the moment. In June, Gazprom drastically reduced the amount of gas flowing through the pipeline before shutting down the route because of annual maintenance. Moscow blamed the cuts on problems with gas-pumping turbines. One of those turbines had been sent to Montreal, Canada, for repairs but couldn’t be returned because of sanctions. Most experts see the turbine issue as manufactured by Moscow, but the Canadian government ultimately granted an exemption for the turbine, which it’s reportedly shipped back. Canada defended its decision, saying it would support Europe’s access to “reliable and affordable” energy as it transitions. Ukraine condemned the move, but allies, including the United States, defended it.

It is unlikely to be enough. On Tuesday, Putin claimed that Gazprom still hadn’t received the necessary documents for the turbine, which meant that while Nord Stream 1 would turn back on, the volumes of gas arriving through Nord Stream 1 would be reduced to about one-fifth of its capacity — although Putin suggested the West only has itself to blame for its sanctions rules. Of course, Putin added, if Europe wanted, it could finally start Nord Stream 2, another pipeline that Germany froze on the eve of Russia’s invasion. But he also indicated that might not even be able to deliver all the gas Europeans want.

That uncertainty is a deliberate play on Putin’s part, and it has forced Europe to plan for a crisis in case Russia continues this pressure. And putting Europe on edge is exactly what Putin wants.

Putin is using gas to try to drive divisions in Europe

Russian gas was a good deal, until it wasn’t. Europe, especially industrial powerhouses like Germany, relied on the cheap and easy access to Russian gas to build up its industries.

Plenty of allies and partners warned that Europe’s deepening energy relationship with Russia was risky, and that Putin could use projects like Nord Stream 2 to undermine Europe’s energy and national security. But some defended the cooperation; Germany, for example, framed Nord Stream as an economic project, separate from its political relationship with Russia. “The partnership is very, very deep, in Germany in particular. But they never, ever thought that there will be a moment where there will be a total disruption, because they saw that as an equal relationship. Russia is giving us natural gas, we are giving Russia money,” Corbeau said.

The Ukraine invasion shattered that notion, but it didn’t change the reality: that Europe still needed Russian gas. This was always a complicating factor when the West sought to punish Moscow for its invasion, and is part of the reason it was so surprising that European leaders punished Russia more aggressively than many predicted before Russia’s escalation. That choice was always going to inflict pain on Europe, too. In some of the debates over sanctions — as with the EU’s ban on Russian oil — divisions started to emerge, with countries like Hungary getting carveouts. Putin is not exactly going to let those slide. “Mr. Putin, he likes to divide and rule,” Corbeau said.

Division, especially, is what Putin is after. The war in Ukraine is nearing the six-month mark. Russia failed in its initial war aims to take Kyiv, but after shifting its focus to the Donbas, it is slowly, but brutally and unforgivingly, expanding its territorial control in the region. Threatening gas supplies to Europe is a tool Putin can use “to split Europe when it comes to sanctions or military assistance to Ukraine,” said Veronika Grimm, member of the German Council of Economic Experts and professor of economics at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23889920/AP22199315938569.jpg)

According to a June 24 poll, 59 percent of Europeans see the defense of European values such as freedom and democracy, as a priority, even if it affects prices and the cost of living. But Putin is banking that as the war drags on, as energy becomes more expensive or harder to get, this opinion will soften.

Putin has been careful to frame the reduced gas deliveries as the West’s fault — it’s the sanctions, or the turbines stuck because of sanctions, that are causing all the problems. We want to deliver the gas, if you guys would just let us. This is also likely why Russia is reducing the amount of gas it sends to Europe, rather than just cutting it off outright. “The picture is that Russia does not violate contracts when it comes to the trade with Europe, but Europe applies a lot of trade sanctions and violates what was agreed upon beforehand,” Grimm said.

“He has the narrative that he can use in order to manipulate opinions in Russia and in third countries and partly also in Europe,” she added.

Europe may feel the brunt of Russia’s pressure, but it will add to the Ukraine war’s economic shocks around the globe. Fuel prices will increase. If Europe’s economy suffers, other economies will suffer, too. Putin is also trying to sell the world that it is the West, not his unprovoked war on Ukraine, that is making things worse for everyone else.

Putin’s strategy may not succeed, but it will be disruptive, even if Nord Stream 1 stays online in some form. No matter the course of the Ukraine war, the energy relationship between Europe and Russia is likely permanently altered. Europe is trying to accelerate its breakup with Russia, but getting gas and oil from elsewhere requires building new infrastructure and new relationships.

Those are all longer-term solutions to an immediate problem. For now, as experts said, politicians and officials must level with the public and take steps to decrease demand. That may mean letting prices go up; that may mean turning down the air conditioner in a heat wave; that may mean choosing which businesses get supplied and which do not.

“It’s going to be painful, but they really have no choice. This chicken is going to come home to roost now or later,” Makholm said. “Russia knows its long-term interests in gas supplies to the EU were dead anyway. And so it’s exercising its maximum pressure right now.”

[ad_2]

Source link