[ad_1]

Nestled deep in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu, cocooned from the world by a young forest, lies a community that wants to change the world. Ask the residents, of Auroville, who come from more than 60 countries, what they are doing there and the answer will be much the same as it has been for more than five decades: “The purpose of Auroville is to realise human unity.”

Auroville was founded in 1968, with a vision to build an international city to upend rigid class and caste systems and be free of the pollution, traffic, chaos, rubbish, social isolation and suburban sprawl that have poisoned modern urban environments.

But over the past few months, harmony has turned to discord over attempts to transform Auroville from a quiet eco-community into a pioneering utopian city.

Lata, a resident of Auroville since the 1980s, said she had “never seen Auroville fractured like this”. “This is the first time such violence has entered the community,” she added. “What about the dream of unity that brought us all here?”

Tensions came to a head last month, when JCBs rolled into Auroville’s forests to begin a controversial development that has created a schism unlike anything seen before in this peace-loving community. Dozens of residents threw themselves in front of the bulldozers, while others backed the demolitions. A case against the project is now being heard by India’s highest environmental court.

“It’s not just valuable trees and buildings that have been bulldozed, it’s the community processes, the unity that holds Auroville together,” said Isa Pieta, 26, who was present. “I can’t believe they would go this far, sacrifice so much in order to get what they wanted.”

The rupture is being blamed by many on an “outsider”. Since 1988, although the Indian government has had jurisdiction over Auroville, the community has been largely left to its own devices. But in July, Jayanti Ravi, a civil servant, arrived as the new secretary of the Auroville Foundation and immediately began enacting the polarising agenda of development.

Ravi’s actions have sent the community into a tailspin; some feel she is giving Auroville the push it needs after years of stasis and dysfunction, others say she is riding roughshod over democratic community processes, and that her agenda is pulling the community apart at the seams.

Many have questioned, too, whether her motives are mired in politics. Ravi has held high-profile positions in Gujarat, prime minister Narendra Modi’s home state, and in 2019, she authored a book that carried a recommendation from Modi on its cover.

In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in Sri Aurobindo, Auroville’s founding guru, by India’s ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Though Aurobindo’s teachings explicitly spoke against the communal politics that have become commonplace under the BJP, there has been a marked attempt by its leaders to champion Aurobindo as an early proponent of the Hindutva ideology, which believes India should be a Hindu rather than secular state. Modi paid a visit to Auroville in 2018.

Many Auroville residents fear the sudden push for development, is entangled in a larger Hindu nationalist agenda to co-opt the legacy of Aurobindo, or to turn their home into a lucrative site for spiritual tourism.

“It is high time Auroville moves forward,” Ravi told the Observer. “It is the 150th birth anniversary of Sri Aurobindo, which India is celebrating, and this development is something which is long overdue.”

Auroville was first dreamed up in the 1920s by Sri Aurobindo, an Indian freedom fighter who became a leading Indian philosopher and guru, and his French devotee and collaborator, Mirra Alfassa, known as “the Mother”. Together in Aurobindo’s ashram in Puducherry they envisaged building a new city where humankind could reach unity.

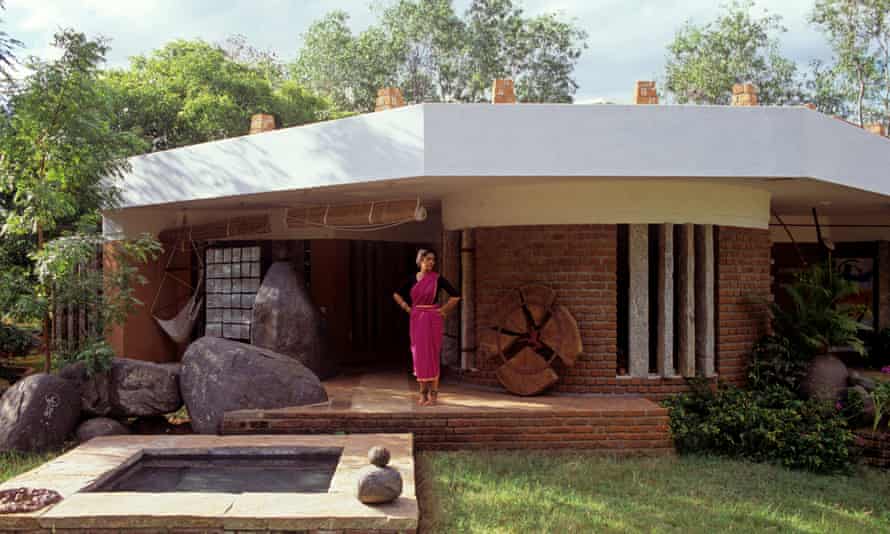

After Sri Aurobindo’s death, Alfassa inaugurated Auroville in 1968 on a barren piece of land a few miles from the ashramWorking with the French architect Roger Anger, Alfassa created the Galaxy Plan, a vision of how a perfect city should be built, designed along a layout of “sacred geometry”. She wanted Auroville to be a “city for humanity” home to 50,000 people, with 75% reserved as a green belt for farming and forest. This was later translated into an official masterplan, which was approved by Auroville residents and the Indian government.

Today, Auroville is home to about 3,200 people, mostly from Europe, India and the US. They have enacted alternative models of currency, land ownership, education and governance, planted over three million trees to revitalise the land and their use of renewables and sustainable ways of living are world-leading.

But in recent decades the city plans have been at a standstill, to the frustration of many. “Nothing has moved because for years we have been stuck between two factions,” said Gijs Spoor, a resident. On one side of the divide are residents who believe Auroville will succeed only if it is built exactly as envisaged in the masterplan, and that any revisions of the sacred geometry, or further delays, would obstruct the Mother’s “forward-thinking vision”.

“This masterplan is more futuristic than we can even imagine, but unless we can build it, what are we here for?” said Anu Majumdar, who has lived in Auroville since 1979. “Trees alone will not solve all the problems of humanity. We are currently 3,200 people living on 3,300 acres of land, which is not sustainable. We need to build the city for 50,000.”

But another group, predominately younger Aurovillians, view the utopian purpose through a different environmental lens and argue that the masterplan, which was last revised and voted on by the community 22 years ago, needs updating.

“We are not anti-development, we are just pro-development in a way that really respects nature, respects the environment, the water, the millions of trees we have planted that are going to decide our survival on this land,” said Pieta, who was born in Auroville. “To refuse to adapt the masterplan because it would be ‘blocking the Mother’s dream’ smacks of spiritual authoritarianism,” she added. “I don’t think it was the Mother’s dream to destroy the living environment around us.”

It was into this impasse that Ravi arrived. Along with a new foundation governing board, also government appointed, a decision was made to begin building the masterplan immediately, starting with a circular road known as The Crown. They also applied for 10bn rupees (£9m) in government grants. “This place is something very beautiful that India has so magnanimously offered and we can not have decadence and stagnation any longer,” said Ravi. “The masterplan was already agreed by residents; it’s my mandate to implement it.”

Alternatives were submitted by concerned residents, but then, without warning, on 4 December, bulldozers arrived in the forest, accompanied by police. That night dozens of protesting Aurovillians stood in their pathway and prevented any demolition. But five days later the JCBs returned and this time razed a 25-year-old youth centre and hundreds of trees.

For many Aurovillians, the manner of demolition – including alleged manhandling of residents – was a violence and division unlike anything that had seen in their community, and the resounding response was one of devastation, shock and pain.

Some residents filed a case against the Auroville Foundation to the Green Tribunal, India’s highest environmental court, which led to an interim halt on all tree felling. And after a petition was signed by more than 500 residents, a request for the development to be put on hold is being debated by the residents’ assembly, a process expected to take more than a month.

The fractures in the community were on full display in a late December assembly meeting. It was the largest turnout in years and descended into chaos. Ravi’s attempt to address the residents prompted uproar. There were shouts of “can we all calm down”, calls for deep breathing and outbreaks of group-chanting of “Om” to try to bring things under control.

Nonetheless, many believe that as splintered as the community is now, the Auroville project is not lost altogether. “The community is fractured but I think out of this darkness has come some good,” said Sandeep Vinod Sarah, a resident who filed the tribunal case. “We are finally energised and confronted with our own divisions. Now is the time for healing.”

[ad_2]

Source link